Things are not looking good in the Himalayas. And it’s not just because of India’s longstanding border dispute with China and recent skirmishes along the Line of Actual Control.

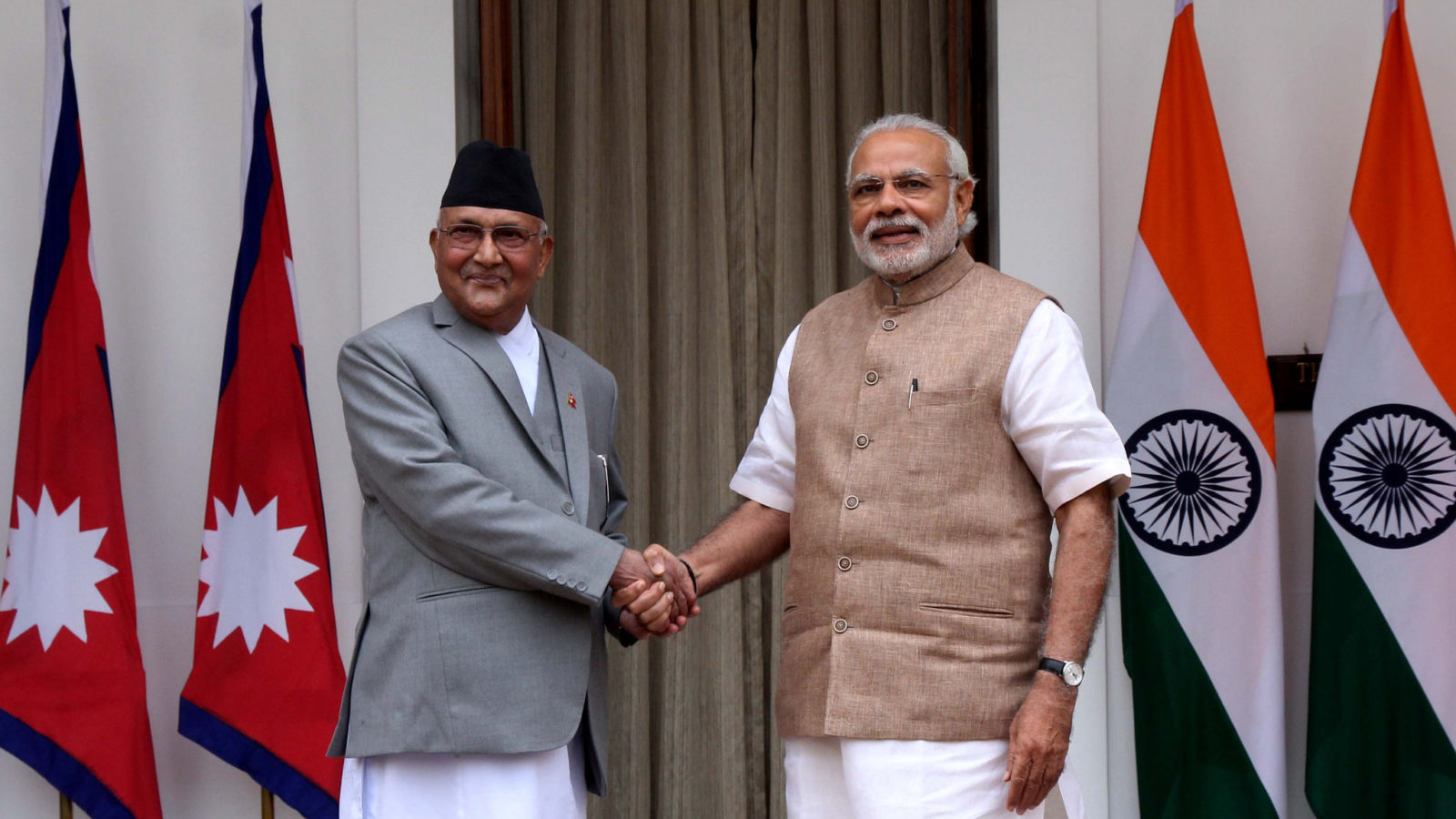

On Tuesday, Nepal’s Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Oli convened an all-party meeting seeking a consensus on amending the constitution to include the strategic northwestern tri-junction with India and China – Kalapani, Limpiadhura and Lipulekh – within Nepal’s territory. It could turn out to be a significant political move, though the amendment has not yet been endorsed by Parliament at the time of writing. Oli obviously wants to negotiate with New Delhi from a position of strength.

Nepal maintains that the 1816 Treaty of Sugauli, ratified by both sides, designates the (Maha)kali as the boundary river. It considers the treaty as the only authentic document on boundary delineation and all other documents as “subsidiaries”.

A lot has changed in Nepal since India’s defence minister Rajnath Singh opened the track linking India and China through the disputed territory on May 8. Battling for political survival amid a serious intra-party feud, the issue with New Delhi has given Oli a new lease of life. For the second time since 2015, New Delhi’s foreign-policy decisions have buttressed Oli’s nationalist credentials.

Here’s a bit of election history. In 2017, Oli’s party, the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) rode to power on a strong nationalist wave, following India’s undeclared border blockade to express its displeasure over the new constitution that it believed wasn’t inclusive enough. After a formal merger between his party and Prachanda’s Maoist party, Oli now heads Nepal’s strongest government in 30 years. If Indian pressure increases, there is a strong possibility that Oli’s nationalist position will trump all intra- and inter-party differences, eroding all nuances. Nepal could yet again be pushed towards China. As of now, Nepal’s strategic community and political leaders are at least wondering why China in 2015 agreed with India to allow the construction of a link road through the disputed Lipulekh. Is China telling us the full story? Does it consider its ties with Nepal independent of its ties with India, an Asia-Pacific power?

In 1963, when Nepal and China signed a border agreement, the two sides decided to remain “open” to Nepal’s both northwestern tri-junction (where Kalapani lies) and for the northeastern tri-junction to be discussed at some point with India. The Indo-China border war had just ended, and there was too much acrimony for all three sides to sit down for talks, recalls Bhek Bahadur Thapa, who was a Nepal government secretary then. When Thapa became Nepal’s ambassador to India in 1997-2003, then prime minister IK Gujral and his counterpart in Nepal formed a joint team at the foreign secretary level to settle outstanding border issues.

When India published a new map in November last year unilaterally, with the Kalapani region within its terroritory, the Nepali side felt that the move breached the status quo and international conventions on the disputed border, argues Thapa. From Nepal’s viewpoint, if inaugurating the Lipulekh track traversing a disputed territory in the middle of a pandemic was bad enough, the Indian Army chief Gen Manoj Mukund Naravane’s claim that Nepal was acting at “someone’s behest” – a clear reference to China – only added to the complications. The Indian position is that the new map was published in light of Ladakh, and Jammu and Kashmir’s changed status as a Union Territory and that the disputed region has always beenin its possession.

As both sides dig in their heels over cartographic interpretations, a political solution is the only way out. The recent border agreement between India and Bangladesh offers a good example.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi got much of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Saarc), and certainly, Nepalis, excited over his “Covid-19 Diplomacy” on March 15 when he convened a videoconference inviting the leaders from the region to work together. But the initiative was subsequently sidetracked due to India’s own battle against the pandemic and, now, upended with the border dispute. All this while, China is seen as being largely successful in containing the outbreak. President Xi Jinping is reasserting himself politically internally and China is projecting its power externally. Nepal continues to import urgent medical supplies from China.

The pandemic offers India, a regional power in its own right, a similar window of opportunity to make its presence felt in the region. A strong case can be made for greater engagement with Nepal, given our vast open border and strong people-to-people ties. Nepali professionals who worked alongside their Indian counterparts after the 2015 earthquake still recall their familiarity of each other’s languages, cultures and even standard operating guidelines (for example, during medical treatment).

New Delhi and Kathmandu need to immediately engage with each other through public diplomacy to bring down the temperature. It could even mean establishing communications at the highest level — between the prime ministers. And with the populations reassured, they can then let their respective bureaucracies handle the issue.

Many in India’s strategic community believe that Oli is playing up the “nationalist card” for his political survival. Some in Nepal also offer a similar analysis. If that is the case, it is all the more reason to resolve the border dispute early. India’s future response will significantly shape the emerging narrative in Nepal. The main opposition, the Nepali Congress and other parties — the Janta Samajbadi Dal, and the Rastriya Prajatantra Party — want to be seen as independent contributors to the solution, instead of giving the impression that they just followed Oli. A hardline approach by New Delhi will further strengthen Oli. India has a difficult choice to make.